Allegretto & Liedtke (2020)

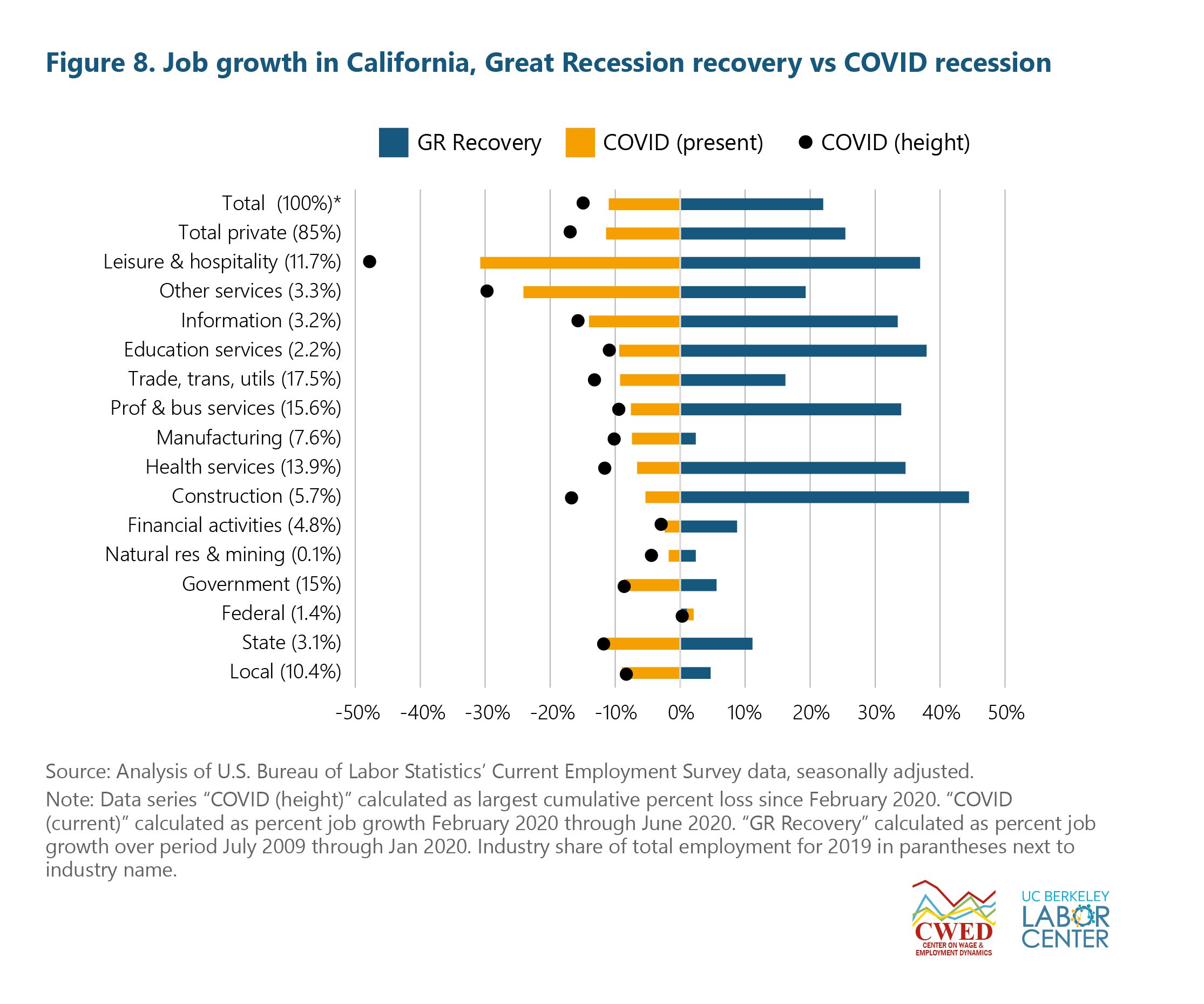

Figure 6 sums up the jobs situation from February through June for the U.S. and California across broad sectors. On a percentage basis, losses in California have been relatively larger than the country overall. For perspective, the U.S. trough of job losses over the Great Recession was -6.3%; in June they were down 9.6% in U.S.

Early in the pandemic, the Golden State shed over 2.6 million jobs (March and April combined) before initial reopening gains of 692,400 over May and June combined—leaving an 11.0% shortfall, worse than the -8.3% height of losses over the Great Recession.

The swift, devastating magnitude of job losses is unprecedented. However, it is important to bear in mind that they are, for the most part, an intentional byproduct of implementing public health precautions. Shuttering businesses and sending workers home were requisite to successfully controlling the spread of the novel coronavirus. Future trends in virus transmission, consumer confidence, and public policy will largely determine when and how quickly affected businesses and their associated payrolls might rebound. Many areas of the United States are currently struggling to get ahead of the virus in a substantive way that would allow for safe, widespread, and sustained reopening. It is likely in the coming months, given the lack of a cohesive national public policy strategy to keep the virus in check, that the trend in jobs may exhibit a two-steps up, one-step back trajectory.

While a hasty rebound is not wholly off the table for the private sector if the virus is controlled to a low and manageable level, a window that appears to be closing, there is little doubt state and local governments will be coping with the pandemic’s fallout for some time. As economic output severely contracted, so too did tax revenues. States, for the most part, must balance their budgets and they are not able to borrow money akin to what is available to the federal government. Thus, without significant relief provided by the federal government, states will face unprecedented challenges in affording the costs of controlling the spread of the virus on top of the usual outlays in running government.

As Figure 6 shows, states have already furloughed or terminated a significant number of public service positions. Overall, public employment is down 6.5% (-1.5 million) and 8.6% (-185,000), respectively, for the U.S. and California. A breakout of the public sector shows a mixed picture. The smaller federal sector is up a bit thus far by 2,500 (+1.0%) in California. However, the lion’s share of public employees (two-thirds) work for local government, where employment has contracted by 9.0% in California. Additional support for the government workforce merits consideration as its workers (e.g., educators, librarians, fire fighters, social workers, construction workers, and park rangers) help to support our communities, provide public education, enhance our lives, and keep us safe.

Simultaneous cuts in public sector budgets and employment, at a moment when more public services are required to address the pandemic, speak to the dire need for greater federal assistance. While the CARES act provided some $150 billion in relief funds for eligible state and local governments, California alone is facing a $54 billion deficit at the state level, composed of a projected $41 billion revenue decline, $7 billion growth in health and human services programs, and an additional $6 billion needed for other COVID-19 related responses.[12] City governments are facing similar woes. For instance, San Francisco announced in May an expected budget shortfall of $1.7 billion over the next two years.[13] Similarly, the City of Los Angeles is anticipating a $1 billion revenue drop through the current year and an additional $1 billion-plus drop through fiscal year 2020-2021.[14] Such figures portend further public sector layoffs in the absence of additional federal assistance.