Driverless? Autonomous Trucks and the Future of the American Trucker

Press Coverage

-

Where are all the robot trucks?

December 4, 2023 - The Verge

-

Autonomous Shockwaves Start to Hit Home

September 1, 2023 - Truck Tech blog

UC Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education

Working Partnerships USA

Executive Summary

Will autonomous trucks mean the end of the road for truck drivers? The $740-billion-a-year U.S. trucking industry is widely expected to be an early adopter of self-driving technology, with numerous tech companies and major truck makers racing to build autonomous trucks. This trend has led to dozens of reports and news articles suggesting that automation could effectively eliminate the truck-driving profession.

By forecasting and assessing multiple scenarios for how self-driving trucks could actually be adopted, this report projects that the real story will be more nuanced but no less concerning. Autonomous trucks could replace as many as 294,000 long-distance drivers, including some of the best jobs in the industry. Many other freight-moving jobs will be created in their place, perhaps even more than will be lost, but these new jobs will be local driving and last-mile delivery jobs that—absent proactive public policy—will likely be misclassified independent contractors and have lower wages and poor working conditions.

Throughout this transformation, public policy will play a fundamental role in determining whether we have a safe, efficient trucking sector with good jobs or whether automation will exacerbate the problems that already pervade some segments of the industry. Trucking is an extremely competitive sector in which workers often end up absorbing the costs of transitions and inefficiencies. Strong policy leadership is needed to ensure that the benefits of innovation in the industry are shared broadly between technology companies, trucking companies, drivers, and communities.

The findings below are based on in-depth industry research and extensive interviews with the full range of stakeholders: computer scientists and engineers, Silicon Valley tech companies, venture capitalists, trucking manufacturers, trucking firms, truck drivers, labor advocates and unions, academic experts, and others.

1. Today, wages and working conditions in trucking vary widely by industry segment

While truck driving is often portrayed as one of the few remaining middle-class jobs that doesn’t require a college degree, Figure 1 shows that the quality of trucking jobs varies significantly across different segments of the industry, which can be split into long-distance and local driving.

Long-distance drivers move goods from factories to distribution centers or retail stores or between distribution centers. Many are working at “for hire” trucking firms, and an important distinction here is whether they are driving a full truckload for a single customer or if their load is a combination of freight from different customers (known as “less-than-truckload”).

Drivers for less-than-truckload firms and parcel companies such as UPS typically have higher wages, better benefits, and stable careers (unionization rates are high). By contrast, full truckload companies tend to pay lower wages, churn through workers new to the industry, and often misclassify their workers as independent contractors (unionization rates are low). Unfortunately, these practices set the competitive standard in key parts of the industry.

Local driving jobs, particularly those driving light-duty trucks, pay significantly less than long-distance jobs. The large majority are local delivery drivers who perform a wide range of assignments, delivering anything from express packages to flowers. They take home salaries that can be half of what long-distance drivers make. The other major category of local driving jobs are at the ports, where drivers work long hours for low wages. When port drivers are contractors rather than employees, they can work the equivalent of two full-time jobs and earn less than minimum wage.

2. Without policy intervention, automation will likely eliminate high- and mid-wage trucking jobs, while creating low-quality driving jobs

Based on an analysis of a range of potential scenarios for the adoption of self-driving technology (see Potential Adoption Scenarios), here are the four ways that automation is most likely to change trucking:

Autonomous trucks are best suited to long-distance highway driving, while humans will still be needed to navigate local streets and handle non-driving tasks.

Many industry experts and developers expect that self-driving trucks will soon be able to drive autonomously on the highway, but that it will take far longer (perhaps several decades) before driverless trucks will be able to routinely navigate local streets packed with cars, pedestrians, cyclists, road work, and other unexpected challenges. Humans will also be needed to handle the many non-driving tasks—coupling tractors and trailers, fueling, inspections, paperwork, communicating with customers, loading and unloading, etc.—that drivers currently perform.

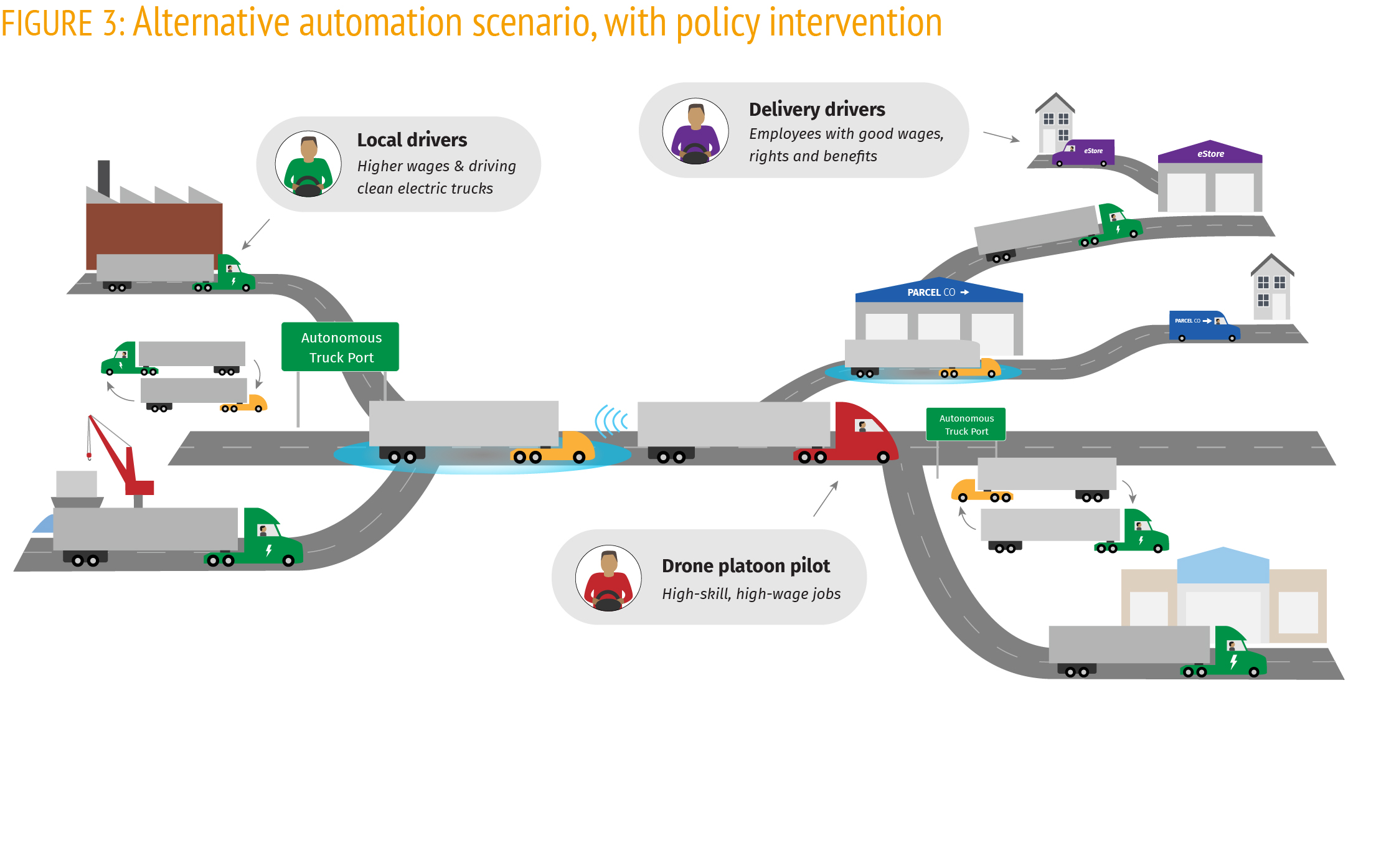

Therefore, the most likely scenario for widespread adoption involves local human drivers bringing trailers from factories or warehouses to “autonomous truck ports” (ATPs) located on the outskirts of cities next to major interstate exits. Here, they will swap the trailers over to autonomous tractors for long stretches of highway driving. At the other end, the process will happen in reverse: a human driver will pick up the trailer at an ATP and take it to the final destination (see Figure 2).

Automation could replace most non-specialized long-distance drivers—about 83,000 of the best trucking jobs and 211,000 jobs with moderate wages but high turnover rates and poor working conditions.

As shown in Table 1, the most likely automation scenario evaluated in this report could result in the loss of an estimated 294,000 trucking jobs. Specifically, self-driving trucks will be best suited for use in industry segments with long stretches of highway driving, minimal need for drivers to perform other tasks, and large firms with the capital to buy (and expertise to integrate) new technologies.

Two parts of the long-distance industry best fit this bill:

Truckload

Truckload drivers typically work for large trucking companies, hauling full trailers over long distances directly from one customer location to another. These drivers rarely perform work such as loading and unloading or caring for special kinds of freight. These characteristics make their jobs more likely to be automated. An estimated 211,000 long-distance jobs in this segment are at risk of displacement from autonomous trucks. As described above, working conditions in this segment are arduous, and turnover is high. Wages are lower than in the unionized segment of trucking and private, in-house fleets, but higher than local delivery driving, the lowest-wage segment of the industry.

Less-than-truckload and parcel

In parcel and less-than-truckload operations, shipments from different customers are combined together at trucking company terminals, driven to another facility near the destination, and then sent out for delivery. The long-distance drivers who haul these combined shipments on the highway rarely do much more than driving, which makes their jobs also vulnerable to automation. Up to 51,000 less-than-truckload drivers are at risk of displacement by autonomous trucks, plus another 32,000 parcel drivers. These are some of the best jobs in the industry, and drivers earn some of the highest incomes in trucking, in part because of high unionization rates. Because these drivers are able to make a career out of trucking, they tend to be older than the average driver and much older than the average U.S. worker.

Over the next several decades, e-commerce growth and lower freight costs could create many new driving jobs, perhaps more than will be lost to automation. Without policy intervention, however, these new jobs will likely have low wages and poor working conditions.

The combination of automation decreasing the cost of moving freight by truck and consumers ordering more goods online and expecting rapid delivery will likely increase the need for local drivers to:

- Move loads to and from autonomous truck ports;

- Shuttle goods from large centralized warehouses outside cities to smaller local depots—the approach being adopted by firms such as Amazon to enable rapid last-mile delivery;

- Deliver packages and other goods to customers’ doors.

However, without proactive public policy, these new driving jobs are likely to be far worse than the jobs that are lost. Drivers bringing loads to ATPs are likely to face conditions similar to those currently experienced by port drivers, such as low pay, long periods of unpaid waiting, and independent contractor misclassification. The port driving sector is rife with stories of drivers putting in 16-hour days but losing money after paying off truck loans, company charges, and other fees. And if local drivers can only afford old and inefficient trucks, more communities are likely to suffer from the high pollution and asthma rates common in neighborhoods near ports.

Delivery drivers, meanwhile, typically take home less than half the pay of better-paid long-distance drivers. Retailers seem increasingly likely to subcontract to small firms with low pay or to adopt the Amazon Flex model of treating delivery drivers as independent contractors who do not receive benefits, must use their own vehicles, and lack the right to organize for higher wages and better working conditions.

Splitting trucking into local human driving and autonomous highway driving is likely to foster the “digitization” of freight matching, with the potential for intense downward pressure on driver earnings.

Currently, long-distance trucking firms rely on complex systems to match drivers with a series of loads, seeking to minimize miles driven without freight, while complying with limits on how long drivers can be behind the wheel. Splitting trips between autonomous trucks that can almost constantly be on the highway and local human drivers who go home each night vastly simplifies this load-matching problem. This approach is likely to lead to the “digitization” of freight, with app-based marketplaces where local drivers can select from available loads.

Digitization could significantly reduce the number of miles driven without freight, saving the trucking industry billions each year. However, the destructive competition of a digitized load-matching system could put intense downward pressure on local drivers’ earnings. To a significant degree, the impact of this approach on drivers will depend on public policy and job-quality standards.

3. Proactive industry and public policy action will be needed if automation is to deliver broad economic, environmental, and social benefits

The way we move goods is going to change dramatically in the coming decades, but how new technologies make their way onto our roads—who benefits, who may be left behind, the impact on our environment—will be shaped by the response of governments, businesses, and workers across the industry. Effective public policy can ensure that trucking evolves into a productive, high-road industry. Policymakers, collaborating with workers and industry leaders, have an opportunity to tackle some of our biggest challenges: creating good, family-supporting jobs, improving road safety, and reducing traffic congestion and carbon emissions. The following three main pillars should drive that collaboration.

Develop an industry-wide approach to worker advancement and stability

Policymakers should create a Trucking Innovation and Jobs Council, bringing together diverse stakeholders across the sector—workers, employers, technologists, and policymakers—to support a 21st-century trucking workforce. The Council would develop and implement an action plan for how industry stakeholders would fund, design, and carry out policies and programs to accomplish two goals: (1) the development of good career pathways and training/job-matching programs for incumbent, dislocated, and future workers; and (2) the creation of safety-net programs to support transitions within and out of the industry, including work-sharing initiatives, supplemental and flexible unemployment insurance, and retirement packages.

Ensure strong labor standards and worker protections

Policymakers should establish a framework of strong labor standards that can shape the impact of autonomous trucks, ensuring high-quality trucking jobs now and into the future. Specific policies include addressing independent contractor misclassification and wage theft; expanding early warning systems in the case of layoffs; and exploring new ways to establish good jobs in the industry and strengthen workers’ right to organize. Some of these policies have long been needed; the goal is to enact them now so that low-wage business models do not become the norm in the industry’s growth segments.

Promote innovation that achieves social, economic, and environmental goals

In order to ensure the best social, economic, and environmental outcomes for drivers, local communities, and our transportation infrastructure, policymakers need to play an active role in regulating the industry and the development of new technology. Examples of specific policies include engaging stakeholders to develop a shared innovation agenda and leveraging public research funding to implement it; allowing state and local governments to experiment with new policy responses; and ensuring that public dollars and policies do not subsidize the displacement of workers.

Suggested Citation

Viscelli, Steve. Driverless? Autonomous Trucks and the Future of the American Trucker. Center for Labor Research and Education, University of California, Berkeley, and Working Partnerships USA. September 2018. https://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/driverless/.